At Sitara Textile Mills in Faisalabad, once a beacon of industrial pride and among Pakistan’s largest textile manufacturers, a haunting silence now hovers where once the rhythmic hum of looms echoed day and night.

Two of its major production units have halted operations — one permanently, the other temporarily — crippled by the economic and energy crisis, which continues to strangle the country’s manufacturing lifeline.

“Nearly 600 workers were affected when these units closed,” says Shahroz Ahmed from Sitara’s human resource department. “The combination of high fuel prices, severe electricity shortages and declining cotton production made it impossible to keep operations running,” he tells Eos.

AN INDUSTRY IN PERIL

Sitara Textile Mills’ story is not an anomaly. The textile and fashion industry, long regarded as the backbone of Pakistan’s economy, is unravelling under the weight of skyrocketing inflation, erratic government policies, global supply chain disruptions and a catastrophic fall in domestic cotton production.

Pakistan’s textile sector, once a global player, is facing an existential crisis as rising power costs and inflationary pressure result in shutdowns and layoffs. At the same time, designer clothes and branded lawns dominate shop floors and Instagram feeds alike, revealing a troubling disconnect...

According to the Economic Survey of Pakistan 2022–23, textiles accounted for about 25 percent of the country’s industrial value-added exports and nearly 60 percent of total national exports. The sector employs 40 percent of the national manufacturing workforce. The magnitude of these numbers makes every factory closure a social tragedy; when one worker loses a job, often an entire family loses its means of survival.

Paradoxically, even as the foundational industry collapses, Pakistan’s fashion consumption is flourishing. During the religious festivals of Eid and in wedding seasons, the frenzy around branded clothing continues to spike. Shoppers throng malls, lawn exhibitions and online platforms, hungry for new collections and deals.

Pakistan’s women’s apparel market, in particular, remains the largest clothing segment in the country.

In 2023, brands such as Gul Ahmed, Khaadi and Sapphire recorded strong sales. Gul Ahmed led the pack with over Rs25 billion in revenue, followed by Khaadi at Rs16 billion and Sapphire at Rs10 billion.

These brands have expanded across the nation. Khaadi now operates in 30 cities through 60 outlets, while Sapphire has over 45 stores. Their presence has also crossed borders, with Sapphire opening outlets in the United Kingdom and the United Arab Emirates, and Khaadi establishing a store in the United States. Despite inflation and import crises, the demand for Pakistani fashion remains unwavering — both locally and abroad.

However, fashion industry insiders point out that the major luxury brands of the country have a loyal clientele among expatriate Pakistanis, which means their revenue continues to grow despite fluctuating sales in Pakistan.

Jaweria Sajid, a university lecturer and social media content creator, exemplifies the loyalty many urban consumers feel toward branded clothing. “I have a tailor phobia,” she laughs. “Brands are more reliable in terms of stitching and design. Even if prices go high, I’d rather increase my income than compromise on quality,” she tells Eos.

Like many, Jaweria views branded wear as an investment in consistency and elegance, even as the textile infrastructure that supports it crumbles.

Figures from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics show that textile exports reached $16.65 billion in 2023–24. Value-added segments such as knitwear, garments and bedwear continue to perform well.

COTTON CONTRACTION CONCERN

Yet there’s an evident shift: exports of raw cotton and cotton yarn are shrinking while demand for finished goods grows. Experts interpret this transition as a move toward value addition, which could be positive in the long-term.

Still, underlying cracks remain. “The local demand for fashion remains high because of our population size,” says Dr Vaqar Ahmed of the Sustainable Development Policy Institute (SDPI). “But the sector is losing global competitiveness,” he tells Eos. “Inflation, rising energy costs and reliance on imported raw materials are all choking us,” adds Dr Ahmad.

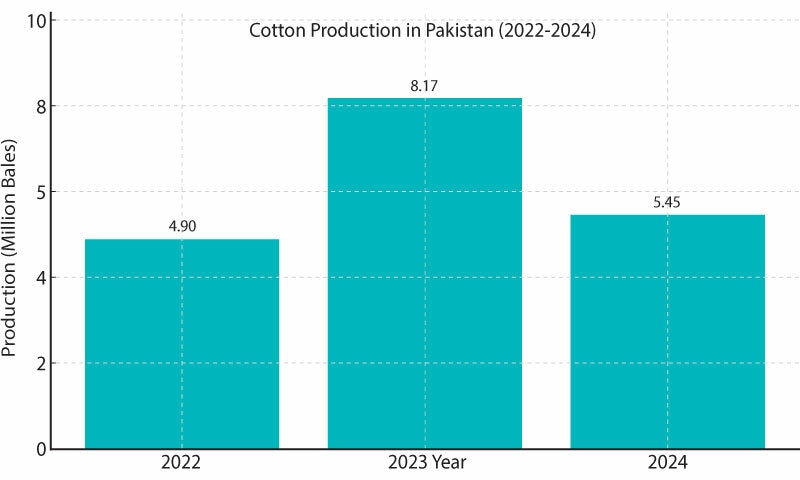

Despite being a cotton-producing nation, Pakistan’s output is collapsing. The Pakistan Cotton Ginners Association reported a staggering 34 percent decline in production during 2022–23 — from 7.44 million bales to just 4.91 million, the lowest in nearly four decades. This shortfall forced local manufacturers to either scale back or import cotton at exorbitant prices, straining already fragile supply chains.

Yasir Ali, owner of Al-Baber Garments and a wholesale dealer in Lahore for 23 years, says this decline has affected his business. “Last year, the fabric quality dropped badly. Prices increased and we couldn’t meet our usual standards,” he tells Eos.

“Exporting is no longer feasible, the Afghan market is gone, and foreign buyers don’t visit anymore,” continues Yasir, whose business specialises in cotton pants and garment. The unavailability of high-quality cotton dealt a direct blow to his production levels.

However, he notes that the demand for children’s clothing remained steady. “Reusing kids’ clothes isn’t very common here. People still spend on children’s wear, which cushioned the impact on our business somewhat,” he points out.

Reflecting on the last Eid shopping season, Yasir adds, “The trend was positive. A stable dollar rate gave people some confidence. Many shopped for Eid and summer at once.”

But looking ahead, Yasir urges the government to create international exposure opportunities. “We need exhibitions in Pakistan where foreign buyers are invited. Our fabric quality is top-tier. All we need is a platform,” he insists.

Policy reform has become a desperate demand across the industry. Dr Sajjad Rashid, who was previously the vice-president of the Faisalabad Chamber of Commerce and Industry (FCCI), paints a grim picture.

“Our production cost has jumped by over 40 percent,” Dr Rashid tells Eos. He also labelled the 18 percent sales tax as unreasonable. “Without immediate relief, a complete collapse is imminent,” he continues.

Dr Rashid blames it on Pakistan’s failure to shift toward synthetic fibres, a pivot that competitors — including China, Bangladesh and Vietnam — embraced years ago. “They’ve modernised. We’re stuck with outdated systems,” he adds.

Dr Rashid reveals that over 100 textile units have shut down in recent years, leading to job losses for nearly 200,000 workers, putting the entire value chain — from tailors to exporters — under stress. “Cotton bale production dropped by over 33 percent and production losses range between 23 percent to 65 percent,” he calculates.

“We have just 6,600 metric tonnes of cotton yarn this year. That’s a disaster,” emphasises Dr Rashid. He believes structural reforms and a targeted export revival strategy are essential. “We are lobbying both federal and provincial governments to introduce relief,” he says.

THE RISE OF THE REPLICA ECONOMY

In parallel with the collapse of traditional industry, a shadow economy of fashion has taken root. On Facebook and Instagram, replicas of designer brands sell at a fraction of the price.

Sellers from smaller towns like Bahawalnagar aggressively market fake Khaadi and Nishat Linen suits to consumers hungry for the branded look. “It’s about identity,” explains SDPI’s Dr Ahmed. “People want to feel they belong to the fashion cycle, even if it’s through knock-offs,” he continues.

The erosion of trust in big brands is pushing consumers toward alternatives. Karachi-based journalist Najia Farzana Lakhani says she’s had enough of poor quality. “Branded clothes used to be worth it. Not anymore,” she tells Eos. A dress from a high-end brand tore after two washes, she claims. “Another sent a defective suit with a messy return process. Now I shop at local markets — better quality, half the price,” says Lakhani.

For skilled artisans and small businesses, survival is a daily struggle.

Khalil Ahmad, a tailor in Sahiwal, built a thriving business after returning from Dubai in 2007. “I stitch branded replicas for clients in the UK and Canada,” he says. “Demand is strong abroad. But rising fabric costs, power cuts, and shipping delays are hurting my business — not my clients,” he tells Eos.

POWER, POLICY AND PRICE TAGS

At the policy level, the warnings are dire. Asif Inam, the chairman of the All Pakistan Textile Mills Association (Aptma), calls the crisis unprecedented. “Gas prices have surged from 852 rupees per MMBtu [Million Metric British thermal units] in 2023 to over 3,500 rupees in early 2025,” he points out.

Electricity costs are 16.7 cents per kilowatt-hour (kWh) — far above regional competitors, continues Inam. “Add in the rupee’s fall and up to 30 percent duties on essential inputs, and we’re in free fall.” Aptma estimates a 30 percent drop in textile orders, which threatens to send further shockwaves through an already broken system.

While being the most influential industry association in Pakistan, Aptma has regularly received criticism for not being a voice for progressive reform in Pakistan. “It has instead opted to remain a very narrowly focussed voice for vested interests only,” says business journalist Khurram Hussain.

Just as the fashion retail boom defies the grim industrial reality, economists warn that this imbalance signals deeper systemic issues.

Dr Mirajul Haq, Associate Professor of Economy at the International Islamic University in Islamabad, is deeply concerned by the decline in Pakistan’s textile industry, pointing out that it has a vital role in the economy — contributing eight percent to GDP, employing 40 percent of industrial labour and accounting for 60 percent of export earnings.

“The industry is shrinking due to factors such as climate change, declining cotton productivity, outdated production methods, inflation, energy crises, and currency depreciation,” he tells Eos.

Dr Haq sees this downturn not just as an economic threat, but as a social one: “This decline is leading to increased unemployment and threatening the livelihoods of millions dependent on cotton,” he points out. “At the same time, the growing demand for high end fashion brands highlights a dual economy, where the local supply side is weakening, while demand for luxury clothing is rising,” he adds.

According to Dr Haq, the textile sector must modernise if it wants to survive. “The industry must adopt modern technology and shift away from traditional business practices to remain globally competitive,” he asserts.

Pakistan’s fashion dream, beautifully stitched on store shelves and social media, masks the reality of a sector stitched together by struggle, shrinking resources and sheer will. Unless serious intervention happens soon, the country risks losing not just an industry, but an entire way of life.

The writer is an investigative journalist and RTI activist.

X: @saddiamazhar

Published in Dawn, EOS, May 4th, 2025