THE country has recently emerged from a war. The Modi government failed to achieve its three intended objects — cowing a nuclear-armed country of 225 million, establishing India as a regional hegemon, and extracting political mileage for its Hindu nationalist constituency. The post-war triumphalism, however, is also exacting a heavy cost on Pakistan’s politico-constitutional order, besides shifting the balance away from a democratic civilian dispensation.

Military courts: On the fateful day — May 7 — when India attacked Pakistan and the country was distracted by the rising din of war, a Constitutional Bench of the Supreme Court, with a 5-2 majority, allowed the trials of civilians in military courts. It overturned the verdict of an earlier five-member bench that had unanimously declared such trials unconstitutional. Whether the military courts can help eradicate terrorism is yet to be seen, though there is little empirical evidence to suggest that ‘military justice’ is an effective tool with which to fight the terrorism which is largely rooted in the political and policy domains. But the military courts will further erode the constitutional trichotomy of power. In ‘Liaquat Hussain’ (1999), the Supreme Court already held that military courts, being part of the armed forces, which are a branch of the executive, could not be allowed to assume judicial power. On another plane though, the validation of civilians’ trial by the military courts betrays the failure of judicial leadership that oversees a large network of antiterrorist courts, which are also equipped with a vast arsenal of special laws to try and punish terrorists.

Reserved seats: The apex court is also seized with another critical matter which could alter the entire political spectrum, particularly the inter-organs balance of power. An 11-member Constitutional Bench is reviewing the Supreme Court’s earlier decision that, on the touchstone of doing ‘complete justice’, gave the ‘reserved seats’ to the PTI. If, however, the bench takes a different and strictly procedural route, and allows most of these seats to the coalition partners, then the latter would get the much-coveted two-thirds majority to further amend the Constitution. Rumours are already rife that the government is contemplating the creation of a separate, more ‘amendable’, federal constitutional court, which will be stacked with ‘preferred’ judges. Thus, the country is once again on the brink. The fate of democracy, including judicial cohesion and autonomy, and citizens’ rights and liberties, hinges on the decision of the Constitutional Bench.

This raises critical questions: for how long will the entire constitutional framework remain vulnerable to an ‘alternative interpretation’ of the law by a different bench of the apex court? And for how long will legal niceties and procedural lapses be employed to trump the ‘will’ of the people?

For how long will legal niceties and procedural lapses be used to trump the will of the people?

Leveraging triumphalism: Historically, post-war euphoria has benefited ambitious or autocratic rulers, unless checked by democracy’s institutional guardrails. Winston Churchill, a World War II hero, lost the postwar elections because people preferred the Labour Party’s sociopolitical agenda in postwar Britain. But history is also replete with many instances of dictators and populists dexterously using wars, regional tensions and national emergencies as tools to strengthen and extend their rule. Our own military and ‘hybrid’ governments have received international recognition and endurance during wars that involved global powers. The ruling elites have used hyper religio-nationalist narratives to camouflage their security failures, gag the opposition and prolong their rule. But in the end, wars, internal strife and emergencies have proven disastrous for the economy, democracy and people’s rights and liberties.

The current ruling elite is also projecting itself, along with the services heads, as the nation’s ‘saviours’. In fact, the newfound triumphalism is being leveraged to achieve four objectives: establish the ruling coalition’s ‘leadership’ credentials; ‘legitimise’ the hybrid regime; appease the military leadership; and more alarmingly, rewrite the Constitution to make both the state and governance more amenable to an authoritarian model.

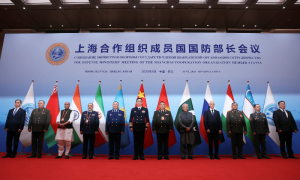

International disorder: Ironically, the Pakistani ruling elites’ increasing authoritarianism resonates globally. The three ills of modern history — autocracy, populism and nationalism — have staged a huge comeback. The international legal order, which took centuries to forge, is unravelling. The world is witnessing a new surge in international wars and internal conflicts. The ‘democracy project’ and ‘nation-building’, which the US-led West used as ‘grounds’ to justify the botched invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, have long been jettisoned by their proponents.

Instead, the old feudal maxim ‘might makes right’ has replaced rules-based international relations, and in many instances, national laws. Dictators, populists, and nationalists are having a field day in much of the world, stretching from India, Hungary, Austria, Russia, Turkey, Italy, China and Argentina to Donald Trump’s America. Capturing state institutions, and then employing them for personal and political gains, is a common feature threading the populist-nationalist-authoritarian model of governance.

Tunnel view: No wonder, our civil-military elites seem surefooted in their efforts to suffocate democracy. All democratic institutions are being steadily toppled, undermining both institutional equilibrium and personal freedoms. Postwar euphoria has further intensified efforts to create a fortress-like political order, in the name of ensuring political stability and economic sustainability. Interestingly, ignoring Pakistan’s financial dependence on the US-dominated IMF, the ruling elites have started extolling the ‘Chinese model’ that stresses economic development, rather than democracy or political freedom.

But drawing parallels with China is ridiculous. China last had a war in 1979. It has since focused only on harnessing the essential ingredients of a booming economy — human capital, leadership, infrastructure, industry, technology, finance, trade and, above all, security. No wonder, it has lifted millions out of poverty. On the contrary, half of our population remains illiterate; the required economic infrastructure and security environment are missing; and foreign investment is thwarted by endemic corruption, bad governance, constitutional crises and political instability. Even then, the state continues to invest in arming and preparing itself for the next conflict — internal and external.

And then it is expected that heavy doses of patriotism will make up for the long-missing requisites of a sustainable and progressive state. This illusionary idea is hard to digest.

The writer is a lawyer.

Published in Dawn, June 4th, 2025