Civil service reforms cannot succeed without local government empowerment. Here’s why

Despite decades of reform efforts and promises, Pakistan’s governance system fails to deliver. Time and again, ambitious agendas are announced, yet institutions remain marred by entrenched inefficiencies, widespread corruption, bureaucratic inertia, and poor service delivery. One may ask, what is it we keep getting wrong? The problem is, we’ve been looking for answers everywhere but within.

While civil service initiatives have been repeatedly proposed and occasionally implemented, their impact has been diluted by an enduring centralisation of power that resists meaningful change. At the heart of the failures lies an often overlooked truth: no reform can truly succeed without a genuinely empowered, autonomous, robust and constitutionally protected local government system.

The case for local government empowerment

Local governments form the foundation of democratic governance and responsive service delivery. They are uniquely positioned to identify and address the specific needs of communities, provide targeted solutions, and enable direct citizen participation. Yet, in Pakistan, these governments have historically been undermined or co-opted by provincial and federal powers that view decentralisation as a threat rather than an opportunity.

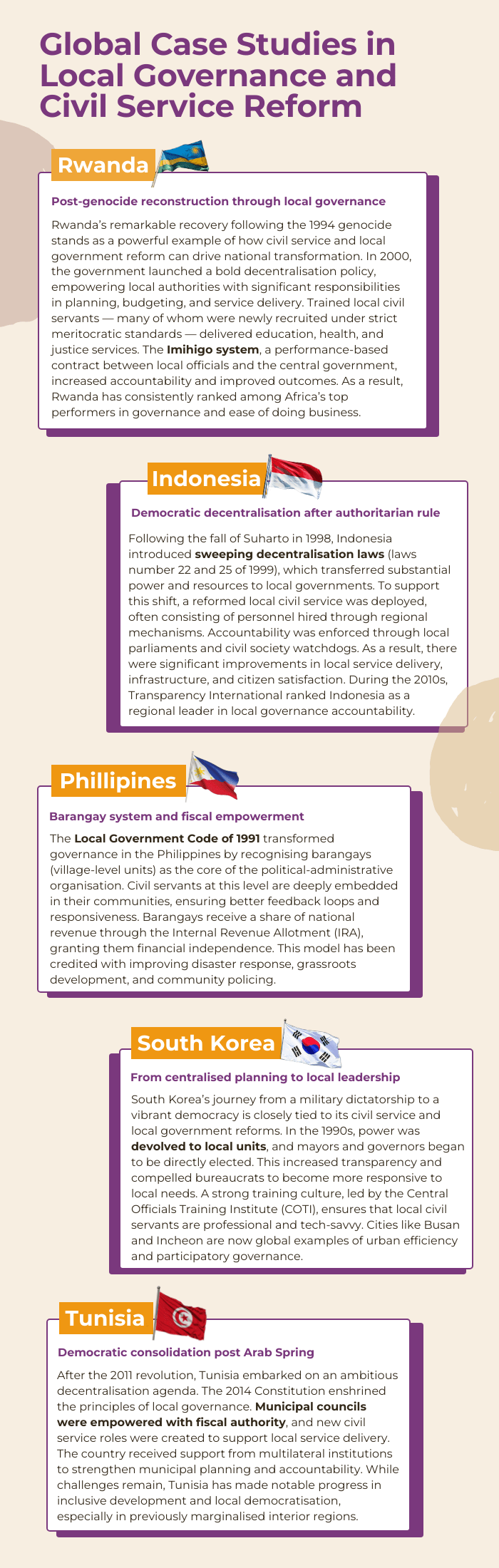

Around the world, decentralised governance has proven its worth. Germany’s decentralised administrative model delegates core services like education and health to local authorities, ensuring responsiveness and efficiency. In Brazil, participatory budgeting, which gives citizens a direct say in local spending, has enhanced transparency and reduced corruption.

In the Pakistani context, academic research has emphasised the strategic importance of local governance. A landmark study on decentralisation reveals that local government reforms often originated from non-democratic regimes — seeking legitimacy rather than lasting institutional change. However, such reforms, including those under Ayub Khan and Musharraf, lacked permanence due to the absence of constitutional backing and the deep entrenchment of central authority.

The Musharraf model and its lessons

General Pervez Musharraf’s Devolution of Power Plan (2000) remains one of the most ambitious local governance initiatives in Pakistan’s history. Implemented through the Local Government Ordinance (2001), the system introduced a three-tier structure — district, tehsil, and union councils — with elected representatives managing local development, finance, and public services.

Under this system, Citizen Community Boards (CCBs) and Musalihat Anjumans were introduced to institutionalise citizen participation and local dispute resolution. For the first time, bureaucrats were made subordinate to elected officials at the local level. However, the lack of constitutional protection meant that the system was dismantled once Musharraf left power. Post-2008 democratic governments did not hold timely local elections, and provincial governments resisted genuine decentralisation.

Despite its flaws, the Musharraf-era devolution revealed the transformative potential of local governance. District governments took ownership of development planning, citizens were engaged in project selection, and marginalised communities had greater access to public services.

Why civil service reform alone is not enough

Civil service reform typically focuses on merit-based recruitment, performance evaluation, training, and reducing corruption. However, without corresponding decentralisation, these reforms are confined to the upper echelons of governance and rarely affect outcomes at the grassroots level.

The Pakistani civil service remains highly centralised, with officers frequently rotated across provinces and ministries. This practice discourages specialisation and undermines local accountability. Without empowered local governments, even the most efficient bureaucrats cannot address local challenges effectively.

Moreover, civil servants in Pakistan often operate in a political vacuum — isolated from the constituencies they are meant to serve. This disconnect hampers their ability to respond to local needs and fosters a sense of alienation among citizens. In my recent article for weekly business and economic magazine Profit, I argue how local institutions can play a crucial role in countering extremism. By delivering essential services, creating employment opportunities, and improving community engagement, they can address the root causes of disillusionment — tasks that remote, centralised bureaucracies are ill-equipped to manage.

A comparative perspective

Across the globe, governments are discovering that the path to national progress begins at the local level.

India’s Panchayati Raj system showcases the power of grassroots democracy. Its local government structure mandates regular elections and assigns significant administrative and financial authority to local bodies. The integration of civil servants in this framework ensures accountability, responsiveness, and deeper citizen engagement.

Turkey’s urban governance is another example. Istanbul’s transformation through empowered municipal leadership illustrates how decentralisation can spur urban renewal, infrastructure development, and economic vibrancy.

Estonia’s e-governance revolution demonstrates the potential of digital integration at the local level. By streamlining services and enhancing transparency, it has significantly reduced corruption and increased efficiency. Countries such as Pakistan can draw on this approach to modernise civil services and empower local institutions.

Here’s what must be done

To truly empower citizens and transform governance from the ground up, Pakistan must reimagine and revitalise its local government systems. The foundation lies in granting constitutional safeguards that mandate regular elections and clearly define the authority of local bodies, with the Supreme Court ensuring provincial compliance. A specialised municipal civil service cadre, as seen in India, can infuse professionalism and continuity into local administration. Equally critical is devolution of finances — empowering local governments with control over property taxes, municipal services, and a fair share of national revenue.

Moreover, digitising administration at tehsil and union levels will bring much-needed transparency, while institutionalising public participation and oversight through citizen juries, community boards, and participatory budgeting will make governance more inclusive. Finally, a performance-based bureaucracy — where civil servants are evaluated on service delivery outcomes instead of tenure or connections — can drive a culture of accountability and effectiveness.

Without such bold reforms, Pakistan risks perpetuating a system that keeps power distant from the people it is meant to serve.

A holistic approach

These examples highlight that local government empowerment, combined with civil service reform, creates a governance architecture capable of addressing complex societal needs. Pakistan can draw valuable lessons from these experiences to navigate its own reform journey.

Civil service reform in Pakistan cannot — and should not — be pursued in isolation. The country’s administrative challenges are deeply intertwined with its political and governance structures. The absence of empowered local governments has not only hollowed out democratic participation but also undermined the effectiveness of the civil service.

To build a responsive, accountable, and citizen-oriented governance system, Pakistan must embrace a dual-track reform agenda: transforming the civil service while simultaneously devolving power to the grassroots. Only then can we hope to resolve the governance crisis that continues to plague this nation. It is imperative for policymakers, civil society, and international partners to support the cause of local governance — not just as an administrative reform, but as a democratic necessity.